Today’s dominant Midwest farming system produces two commodities—corn and soybeans—in abundance. But this system has grown steadily less beneficial for farmers over time. US corn and soybean growers achieved record-high harvests in 2016. But due to oversupply, prices for these crops have plummeted, and US farm incomes are expected to drop to their lowest levels since 2002.

The two-crop system falls short in the sustainability department, too. It typically leaves fields bare for much of the year and uses plowing practices that result in unsustainable levels of erosion. It relies on heavy fertilizer use, which allows excess nitrogen to escape into our air and water, costing the nation an estimated $157 billion per year in human health and environmental damages.

Rural communities suffer many of these consequences. Iowa, for example, ranks high in surface water pollution from fertilizers, pesticides, and eroded soil. And the negative effects extend far beyond the Midwest: Corn Belt watersheds are major contributors to the annual “dead zone” in the Gulf of Mexico, and emissions from agricultural soil management make up 5 percent of the US share of heat-trapping gases responsible for climate change.

Higher yields, less pollution

How can farmers maintain productivity and profitability while protecting soil and preventing pollution? Researchers at Iowa State University have an answer: modified cropping systems.

Since 2003, these researchers have compared three rotation systems: the region’s typical two-year corn-soybean system, a three-year system that adds a cool-season small grain (such as oats) with a cover crop of red clover that acts as a “green manure,” and a four-year system that includes a small grain (again, oats) with a green manure of alfalfa, followed by a second year of alfalfa for harvest.

The researchers have found that the longer rotations enhanced yields and profits while reducing pesticide use and pollution. Compared to the standard corn-soy rotations:

- Average corn yields were 2 to 4 percent higher

- Average soybean yields were 10 to 17 percent higher

- Longer rotations were just as profitable as corn-soy alone

- Herbicide use was reduced by 25 to 51 percent

- Herbicide runoff in water was reduced by 81 to 96 percent

- Nitrogen fertilizer application rates were reduced by 43 to 57 percent

What UCS found

Can we expand these diverse cropping systems sustainably? And where will the benefits be greatest? Our analysis addressed these questions. According to our modeling, adopting diverse rotations grown without tillage (plowing) in the 25 Iowa counties with the most erodible soils would achieve dramatic results:

- Reducing soil erosion by 91 percent compared with tilled corn-soy

- Saving taxpayers and downstream communities $196 million to $198 million per year in surface water cleanup costs

- Net reductions in heat-trapping gases valued at $74 million to $78 million per year

Scaling it up

We also analyzed the extent to which Iowa’s farmers could scale up this system across the state, finding that:

- Diverse crop rotations could be adopted over time on 20 to 40 percent of Iowa’s farmland without changes in crop prices driving farmers back to predominantly corn-soy

- Soil erosion would be reduced by 88 percent compared with tilled corn-soy, to a sustainable level given natural soil replacement rates

- Taxpayers would gain a total of $241 million to $505 million in environmental benefits every year

What's in the way?

So why aren’t farmers already adopting these economically and environmentally beneficial systems? As business people often operating on slim margins, farmers face numerous barriers to adopting modified crop rotations:

Market barriers. Markets for oats and other small grains are not as well developed as markets for corn and soybeans. Demand for these commodities is lower, and infrastructure is in shorter supply. We assume that new markets for these crops will emerge to meet supply over time, but farmers may initially be daunted.

Financial barriers. Adding new crops to farmers’ usual rotations may require significant up-front investments and raise costs in the short term. And for the majority of US farmers who rent farmland from others, typical short-term leases do not allow for long-term planning or provide incentives for soil and water quality improvements.

Crop insurance and credit constraints. Until recently, federal crop insurance programs have discouraged complex rotations. In 2014, Congress extended coverage to diversified farmers with a new Whole Farm Revenue Protection program. But many county insurance agents lack training on this program and may not recommend it to farmers who could benefit from it. And lenders unfamiliar with the potential profitability of longer rotation systems may be unwilling to make the loans that farmers need in order to adopt them.

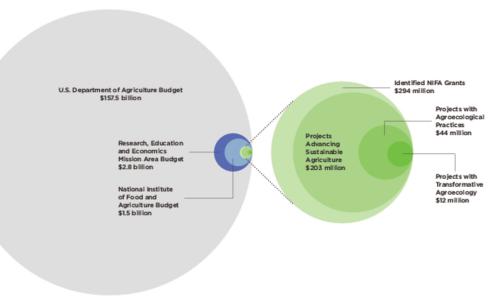

Technical and information barriers. Farmers need evidence that they can adopt new practices successfully and profitably. Publicly funded research programs are critical, but such research is severely underfunded at the USDA and at public universities. Farmers also need publicly funded technical guidance, yet the number of county-level agricultural extension agents tasked with advising them has declined in recent decades.

Recommendations

Federal farm policies have played a major role in creating the dominant corn-and-soybean cropping system in the Midwest. Changes to these policies and investments are now needed to shift this system. Policymakers should:

- Expand incentives and strengthen up-front financial support for farmers to shift to diverse rotations. Specific recommended changes include stronger support in the Conservation Stewardship Program (CSP) for diverse crop rotations, increased support for rotations in the Environmental Quality Incentives Program (EQIP), and additional funding for USDA Farm Service Agency loans.

- Strengthen crop insurance coverage for diversified farms through improved promotion of the Whole Farm Revenue Protection Program. The USDA must do more to promote this new and unfamiliar program to farmers and insurance agents.

- Increase public support for research, technical assistance, and demonstration projects on diverse rotations. A greater understanding of the optimal diversified farm system in regions throughout the country will increase practical understanding and adoption of crop rotations. Additionally, more research needs to be devoted to how livestock producers can best incorporate different crops into their livestock feed. This requires full funding for the USDA’s Agricultural Food and Research Initiative (AFRI), funding more long-term research, and developing a new farm pilot program to increase practical understanding of diverse crop rotations and their potential benefits for farmers and livestock producers.

(For a more detailed discussion of these recommendations, download the report PDF.)